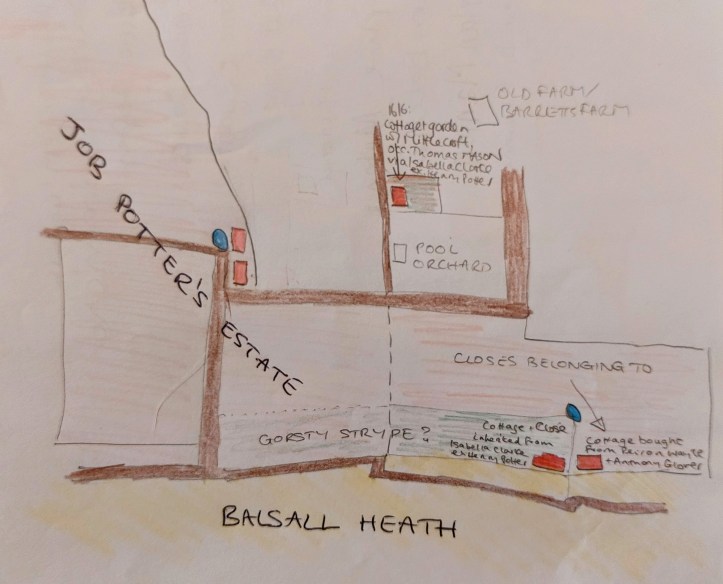

This ancient cottage with its single croft (marked in blue on the map) was adjacent to the cottage known today as Emscot (orange circle). Between 1750 and 1783 it was the site of the short-lived Berkswell Quaker Meeting, which gave its name to Meeting House Lane. It was sold in 1891 and replaced with a grand pair of semi-detached Victorian villas (marked with a blue circle on the map).

Early Years

In January 1615/16, a Berkswell widow called Isabel Clarke made her will, leaving everything to Job Potter, the small son of her ‘kinsman and kinswoman’ Thomas Hooke and his wife Mary.1 Her estate included ‘my cottage or tenement with the close to the same belonging called the Gorsty Strype,’ which she had recently bought from Job’s father and Mary Hooke’s first husband, Henry Potter.

Seventy years later in 1686, Job Potter made his own will. Among his fields was ‘Kendole Field, with part of the Gorsty Strype now laid to it,’ and among his properties a ‘cottage and croft’, which he bequeathed to ‘Thomas (III) Byfield, weaver, son of the late Thomas (II) Byfield‘.2 It was ‘now or late’ occupied by ‘Widow Hands,’ perhaps the ‘Elizabeth Hands, widow‘ who was buried at Berkswell in 1697.

This map of Job Potter’s estate shows the cottage at the bottom of the map (the left of the pair), with a hypothetical location for the ‘Gorsty Strype’ (Gorsey Strip). It would make sense for a strip of gorse-covered land to run alongside (and perhaps have been reclaimed from) the Heath.

When Thomas (III) died in 1704, he left ‘my dwelling house and close with barning and outhouses’ to his eldest son, Thomas (IV) Byfield, subject to a payment of 25 shillings a year to his widow, Mary.3 Thomas (III)’s probate inventory records that his home had a parlour, kitchen, buttery and weaver’s workshop downstairs, with rooms upstairs over the parlour and shop and at the ‘staires head’. Outside were a brewhouse, stable, and barn.4

Thomas (IV) and his wife Alice mortgaged their ‘house and close’ at ‘Olna End’ in 1711 and again in 1715.5 It isn’t clear how long they themselves lived there, but until at least 1735 it was home to Thomas’s mother Mary, now Mary Mowsley and widowed for a second time. In April 1735, Mary’s stepson William Mowsley sold the cottage to a widow from nearby Lapworth called Anne Wheeler.6

The Berkswell Quaker Meeting

The Wheeler family had Quaker connections and it is during the tenure of Ann Wheeler, who moved from Lapworth to Berkswell, and her eldest son John, a linen weaver, that the cottage became home to the small and short-lived Berkswell Meeting (c. 1750-1783).7

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Berkswell Meeting was an offshoot of the larger Coventry Meeting. It was never very large and survived for only a little over thirty years.8 The meeting records (available via subscription on www.findmypast.co.uk) show that Berkswell celebrated around eight marriages between 1755 and 1769. Although most of the families had no obvious Berkswell connections, regular witnesses included John Clark, a leading Quaker of Balsall Street. The only Quaker birth recorded at Berkswell was that of William, son of Christopher and Elizabeth Bradnock on 20 September 1760, and the only burial that of Christopher Bradnock, linen-weaver of Berkswell, who was buried ‘in the Friends Burying-Ground at or near their Meetinghouse at Berkswell’ on 20 May 1788.9

In 1778, John Wheeler sold the cottage to the leading Coventry Quaker Edward Gulson, and in 1779, Gulson sold it to his fellow Friend John Clark.10 The tenant after Wheeler left was William Robinson who was the ‘gravemaker’ for Berkswell’s only Quaker burial.11 Robinson was still in residence in 1794 when Clark’s heirs sold the property to a grazier from Balsall called Job Findon.12

A Farmhouse again: growing the estate

Job Findon would live and farm at the cottage for 30 years. A member of the large Findon family of Claverdon, he had lived in Balsall as a young man before taking several short-term tenancies in Oldnall End, including Manor Cottage (1783-90). As a widower with no children he did not need the entire cottage, which seems to have been divided in two, with Findon occupying one part and the Robinsons remaining in the other.

After buying the cottage and croft in 1794, Findon used the Enclosure Act of 1802 to expand the estate. He received a new allotment of land (1R 13P) on the common opposite his cottage, an old encroachment between the cottage and the newly laid out Meeting House Lane, and a ‘private road‘ of his own, leading from the new lane into his foldyard (all marked in green on the enclosure map below). In 1810, he purchased the large field over the road from Thomas Tidmarsh (marked in purple on the maps below).

Orange is the original holding; green old encroachments and purple new enclosures

The old encroachments of 1802 have been absorbed into the larger holdings.

In 1824, Findon sold the newly expanded estate to William King, a ‘gentleman’ from Balsall,13 who sold it on again six years later. The 1830 sales particulars describe it as two messuages or tenements, with the outbuildings, garden and three closes of excellent arable and old pasture land adjoining, occupied by a yearly tenant called Peter Goode with his wife Lucy.14 The purchaser was a young farmer and pig dealer from Balsall, called James Taylor, who moved in with his wife Mabel and their growing family.15

The Taylors turned the cottage back into a single dwelling. The 1839 Tithe Apportionment shows Taylor as owner of the ‘house and garden with site of Quaker Meeting (964), Pleck (965; this is the original croft incorporating the old encroachments from 1802) and two fields called Balsall Slang (966-7), all occupied by Thomas Sedgeley while the Taylor family were spending a short period in Coventry. The Taylors were back in residence for the 1841 census, which records James (55, farmer) with Mabell (40) and children Elizabeth (12), Joseph (9), Mary (5), twins Sarah and Jane (2) and baby James (3m) along with a 15-year-old servant, Thomas Adkins.

In 1847, Taylor sold the farm, described as ‘a messuage heretofore two messuages,’ to an innkeeper from Exhall called Thomas Moore for £490.16 Moore rented the farm to a series of tenants, including William and Elizabeth Goode (1851),17 William and Sarah Deemin (c.1857-1864), and James and Ann Gibbs (1871-1891). During the Gibbs family’s tenure, the farm grew to 29 acres, incorporating more of the farmland between Meeting House Lane and today’s Kenilworth Road.

The End

After the death of Moore’s son and heir William in 1891, the estate was sold to a blacksmith from Hampton called Thomas Poole.18 The farmland to the south of Meeting House Lane remained in use, but the cottage was demolished and two large semi-detached villas built in its place, which in 1900 were called Ivy Bank and Sunnydale (today nos. 81 and 83). The adjacent croft, which had been attached to the cottage for over 200 years, was let out to the owners of Ivy Bank as a paddock.19 Today the croft has been built over and there is nothing left of the original cottage, but its short time as home to Berkswell Quaker Meeting is remembered in the name of Meeting House Lane.

Notes

- Will of Isabel Clarke of Berkswell, widow. 26 Jan. 1615/16. Probate 15 Oct. 1616. Consistory Court of Lichfield & Coventry. ↩︎

- Will of Job Potter of Berkswell, yeoman. 6 Dec. 1686. The generational markers assigned to the various Thomas Byfields are my own. ↩︎

- Will of Thomas Byfield of Berkswell, weaver. 14 Feb. 1704. ↩︎

- Probate Inventory of Thomas Byfield of Berkswell, weaver. 24 Feb. 1704. ↩︎

- Deed and Final Concord between Thomas Byfield of Berkswell, weaver, and his wife Alice, and Benjamin Tristram of Fillongley, clerk. 22 May 1711. Coventry Archives PA 242/10/2-3. ↩︎

- Lease and Release by William Mowsley of Balsall, yeoman, to Ann Wheeler of Lapworth, widow. 7-8 April 1735. Coventry Archives PA 242/10/8-9. ↩︎

- In 1824, an 83-year-old carpenter called George Smith who had known the Wheelers personally gave a sworn declaration to their ownership and residence as part of a later property sale. Warwick Record Office CR 2660/35. ↩︎

- For the history of Berkswell Quaker Meeting see William White, Friends in Warwickshire in the 17th and 18th Centuries (1873), pp. 136-138; ‘Meeting Houses Built and Meetings Settled: Answers to the Yearly Meeting Queries, 1688-1791, with notes by David M Butler,’ The Journal of the Friends’ Historical Society 51.3 (1967), p. 204. ↩︎

- Christopher Bradnock’s burial took place after the Berkswell meeting had officially closed in 1783. The documentation in the burial book is a request to ‘William Robinson, Grave-Maker’ to ‘make a grave on or before next 3rd day, in Friends Burying-Ground, at or near their Meetinghouse at Berkswell’ for Bradnock’s body. I have found no other reference to a burying ground at Berkswell, although William Robinson is confirmed by other records to have been resident in the cottage at the time. ↩︎

- Lease and Release from John Wheeler to Edward Gulson, 12-13 Feb. 1778; Lease and Release from Edward Gulson to John Clark, 1-2 April 1779. Coventry Archives, PA 242/10/10-13. ↩︎

- See note 8. ↩︎

- Lease and release from Joseph Seymour and Thomas Clark Smart to Job Findon, 28-29 Mar. 1794. Coventry Archives, PA 242/10/17-18. ↩︎

- Lease and release from Job Findon to William King, 28-29 Sep. 1824. Warwick Archives, CR2660/36-7. ↩︎

- Warwick Advertiser, 5 Jun. 1830: 2. ↩︎

- Lease and release by William Lewis and Thomas Reeve [King’s trustees] to James Tayl;or, 10-11 Oct. 1830. Warwick Archives, CR2660/42-3. ↩︎

- Conveyance by James Taylor and the Rev. James Packwood (the mortgagee) to Thomas Moore, 22 Oct. 1847. Warwick Archives, CR2660/44. ↩︎

- William was the son of Peter Goode, who had rented the farm in 1830. ↩︎

- Conveyance by Maria and Sarah Moore to Thomas Poole, 30 Sep. 1891. Warwick Archives, CR 2660/54. ↩︎

- ‘Auction,’ Coventry Herald, 8 Jun. 1900: 4. ↩︎