A couple of weeks ago this one-place study turned six months old (you can read my original post here) and its author turned … a rather bigger number (!). In celebration of both, I decided to spend the morning at Warwickshire County Record Office taking my first look at an entirely new-to-me resource: manorial records.

What are manorial records?

They are the organisational records of individual manorial estates! A manor or manorial estate was an administrative unit under the feudal system that arrived in England with the Normans. Each manor was centred around a manor house, occupied by the Lord or Lady of the Manor. The manor likely owned a great deal of land and property, which it rented out to local people, who became manorial tenants. Their tenancies (and many other aspects of their lives) were managed through a system called the manorial court. As I learned, manorial court records are a brilliant resource for learning about the lives of ordinary people on the manorial estate.

Oldnall End in manorial records: where to start?

Oldnall End sits within the Manor of Berkswell, whose records according to the Manorial Documents Register are divided between Warwickshire County Record Office and the National Archives. As you can see from the MDR, the earliest available records for Berkswell Manor are some keeper’s accounts from 1437-1438, but I wasn’t quite brave enough to start with those. My One Place Study is organised around properties, so manorial property records in the form of the minutes of the Court Baron seemed like an ideal place to start.

Berkswell’s Court Baron met annually on Easter Wednesday, chaired by the Steward of the Manor, with a jury (called the ‘Homage’) of up to 12 local men. It almost exclusively covered property transactions, recording the transfer between tenants of the manor’s farms, fields and cottages. Manorial property was held on what was called a ‘copyhold’ basis as opposed to freehold property, which was independently owned. Copyhold tenants could sell, sublet and bequeath their properties within certain restrictions, and the books and rolls of the Court Baron record these transactions.

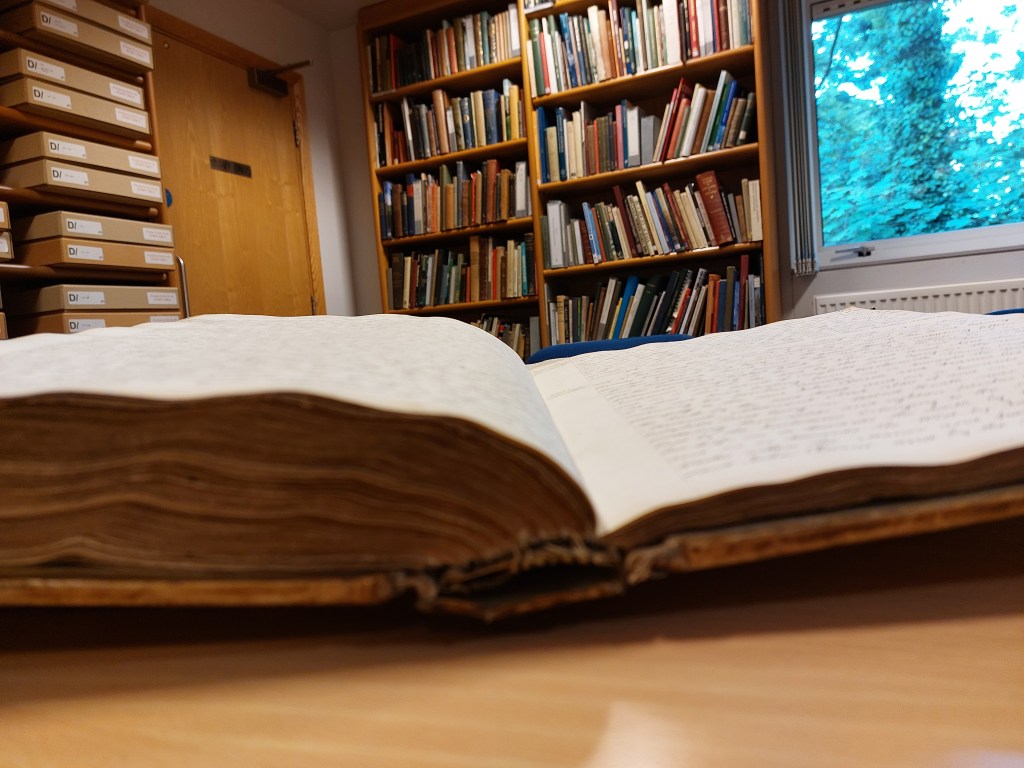

Being a manorial records newbie, I wasn’t quite brave enough to dive straight into the original records, so I began by consulting a 19th-century name index to the Court Books and Rolls, covering the period 1586-1819. The unnamed indexer did a sterling job of summarising transactions, including surrenders (sales), admissions (purchases), the ‘finding‘ (naming) of heirs, the ‘presentation‘ (acknowledgment) of deaths, and the admission of widows and widowers on the death of a spouse, which is charmingly called ‘admission to his/her free bench‘. Here’s one example, which relates to a cottage on Kelsey Lane:

Esther Riley, widow, found intitled to her Free Bench as Widow of Rich Riley and admitted; Thomas Riley found heir of Richard Riley and admitted. 6 April 8 Geo 3 [6 April 1768].

What did I find?

Basically, lots and lots of property transactions! I worked my way through the index (organised by surname) and transcribed all the entries connected with Oldnall End. Then, back home with a fortifying cup of tea, I set to looking for connections and building chains of property transactions. Want to see an example? Of course you do!

This is Manor Cottage, on the corner of Station Road and Sunnyside Lane. The 1839 tithe apportionment records it as a cottage, garden and two crofts owned by John KELSEY and occupied by Thomas MARLOW. With the help of the court records (supported by Land Tax, wills and other documents), I was able to trace its owners and occupiers back around 120 years:

The Kelseys, 1814-1882. The cottage came into the Kelsey family at the 1814 Court Baron when John’s unmarried sister Sarah lent the occupier James WOOD a mortgage of £140. James died in 1815 and his widow couldn’t repay the money, so ownership passed to Sarah. The cottage stayed in the Kelsey family (and occupied by the Marlows) until it was sold in 1882.

The Woods, 1798-1820. James and Elizabeth WOOD had come to Berkswell from Stoneleigh and moved into Manor Cottage by 1798 (land tax). After James’s death in 1815, Elizabeth (‘Widow Wood’) stayed until 1820 (land tax).

Ann Banwell/Bury, 1790-95. Ann Banwell took over the property at the 1790 Court Baron: Job Findon, yeoman, surrenders a tenement and two closes purchased of Goodall by Henry Watson, later of Joseph Watson his son to Ann Banwell of Kenilworth, spinster. Later that year Ann married James Bury. The 1795 land tax records Mrs Berrey as owner and William Clifton as occupier.

Job Findon, 1783-90. Job is recorded as occupier on land tax from 1783, but he formally took over the tenancy at the 1789 Court Baron: Joseph Watson of Cubbington, cordwainer … surrenders a tenement and two closes … purchased of Goodall by Henry Watson, father of Joseph … to Job Findon of Barkeswell, yeoman. Admitted. Although he was in residence for seven years, Job only formally held the property for a year.

The Watson family, bef. 1766-1789. The Watson family had long owned the house that is now the Brickmaker’s Arms just down the hill from Manor Cottage. Henry Watson purchased the neighbouring cottage and two closes sometime before 1766 from the Goodall family; by his will of 15 January 1766 he left it in turn to his sons John and Joseph, who rented it out to tenants including Thomas Docker and Job Findon (land tax).

The Goodall family, 1719-bef. 1766. The Goodall family was in residence by 1719, when Joseph and Elizabeth Goodall, with Joseph’s mother Mary, were formally admitted: Mary Banwell, formerly the wife of Jos. Goodall, dec’d & Jos Goodall, son of Jos. surrender tenements in Oldnall End ot the use of Mary & rem. to Jos & Eliz Goodall. Admitted.

We don’t (yet!) know when the Goodall family took on the property, but Manor Cottage closely resembles other early 18th-century properties in the village, so it’s possible the cottage was built during their tenancy.

What next?

The next step is to look at the original Court Books and Court Rolls, which should have more detailed descriptions that will help me identify the properties I haven’t yet been able to pin down. I also want to look at a manorial survey of 1553-54, which will hopefully include a map – but that will involve a trip to the National Archives (and also reading 16th-century handwriting…). In any case, I won’t be waiting till my next birthday for my next visit – now I’ve been bitten by the manorial bug there’s no going back!

[…] like Moat Cottage or Manor Cottage prolific evidence is available of sales and inheritance via the manorial court rolls, whereas for a freehold property like Cherry Tree Cottage, the primary sources – at least […]

LikeLike

[…] I put on my local history goggles and tracked down some lost cottages in our local park. I had my first encounter with manorial records and learned about court rolls and copyholds. I spent a worrying amount of time delving into probate […]

LikeLike