I’ve had a lovely day today finishing off the history page for the 17th-century farmhouse on Station Road which we know today as the Brickmakers’ Arms, or the Brickies. It’s part of my project to produce a brief history and chronology of every property in Oldnall End, although I’m swiftly learning that some are MUCH easier to track than others! This is especially true when there is lots of evidence available from wills, inventories or (in the case of copyhold properties), court rolls. In the case of the Brickies, there is wonderful detail available from probate inventories, and since I couldn’t fit it onto the main house history page without condemning you to endless scrolling, I decided to share it here.

Why I heart Probate Inventories

Probate inventories are one of the most fascinating sources for learning about everyday life in these cottages and farmhouses. They are essentially a list and valuation of all a deceased person’s belongings, from clothing and cash, via furniture and household goods, to livestock and crops in the fields. An inventory was usually carried out within a few days of a person’s death, and the assessors were often neighbours, who walked through a property room by room and listed everything they found (that’s certainly the case for most of the Oldnall End inventories I’ve found). While we find probate inventories in all periods, they were especially common between the mid-16th and mid-18th century.

The first two Watsons to own the Brickies both left detailed probate inventories: William (I) WATSON in 1704, and his son Henry (I) WATSON in 1729. The detailed, room by room inventories allow us an insight into the house and its furnishings during the first quarter of the 18th century. And even better than that, by comparing William’s and Henry’s inventories, we can imagine each room and the changes it underwent over a quarter of a century. It’s so vivid!

While the earliest generations of Watsons were in residence, the house had four dwelling rooms (parlour and hall downstairs, with upstairs chambers over) and two service rooms, most likely on the ground floor (dairy and cheese chamber). In 1704 the cockloft, or roof space is listed and used for storage; although it isn’t mentioned in 1729, it must still have existed even if no longer used.

Let’s follow the assessors through the house…

The Hall

Source: V&A Museum Collection

The Hall was the main living and cooking space for both William and Henry and the only obviously heated room. It was furnished with two joynd forms (benches),1 chairs (six in 1729), fire utensils and cooking implements. The furniture changed very little between 1704 and 1729; William’s inventory records two tables, but Henry had reduced this to just one ‘long table’, while his father’s gun has disappeared from the inventory.

The fire and cooking utensils in 1704 are listed as: a jack, a dripping pan, 2 spitts, a frying pan … and other things. By 1729, the list is more extensive: firelinks and hooks, one paire of Bellowes, fire shovel and paire of tongues, and one fryeing pan. Also stored in Henry’s hall was his pewterware (14 dishes, 2 flagons, 2 candlesticks), his brassware (2 ladles, 1 skimmer and a fleshfork) and heatware (7 kettles, 1 brass pot, 1 brass pan and a warming pan).

The Parlour

A parlour at this time was an additional downstairs living space that could also function as a bedroom. William’s parlour in 1704 was evidently a sleeping space, since it contained a bed which was perhaps a four-poster, since it had curtains as well as the expected blankets, bolster and coverlet. The screen may have been there to give privacy to the bed, since the room was evidently furnished to host many people, with six chairs and five joynd stools. There were also two tables, a joynd cupboard and a press cupboard, the latter likely for both storage and display.

Source: V&A Museum Collection

25 years later, Henry’s parlour was almost unchanged, although the furniture had thinned out a little, with one table, one cupboard and the screen either disposed of or unrecorded.

The Parlour Chamber

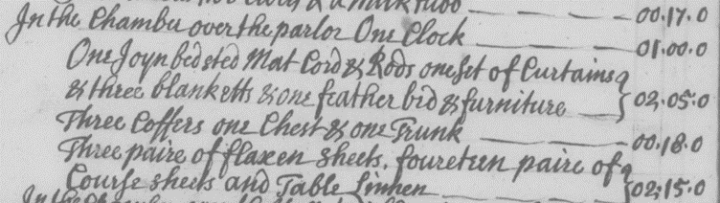

Source: Find My Past

The room above the parlour was another sleeping space, with at least two beds in 1704. One was another four-poster with two blankets, coverlet and curtains. The other was William’s own bed, which he bequeathed to son William in his will as ‘the bed I now lye on.’ It is described in the inventory as ‘the bed he dyed on & the other bed which he gave to William his son, with the Furniture belonging to them’. The ambiguous wording suggests that there may actually have been two additional beds – William’s normal bed and another where he died. As well as a sleeping space, the parlour chamber was used for storage, with three chests, two coffers, a box, a cupboard ‘and other things.’

Source: Find My Past

25 years later, the chamber was a little less cluttered and a little more comfortable, but still a combined sleeping and storage space. William’s bed has gone and Henry has just one bed, now described as ‘one joyn bedsted, mat cord & rods’ with ‘one set of curtains & 3 blanketts & one feather bed & furniture.’ He also has his father’s large clock (valued at £1), which was listed but not located in 1704 so may have been in the chamber all along.

This chamber in 1729 was used to store linen: there are 17 pairs of sheets (3 flaxen, 14 ‘course’) and table linen, presumably stored in one of the 3 coffers, 1 chest and 1 trunk. In 1704, the linen is listed but, like the clock, not ascribed to a room – so perhaps it was here all along. The earlier inventory lists 19 pairs of sheets (whether flaxen or coarse is not recorded), ‘two dozen and six napkins,’ 3 table cloths, 3 pillow biers and other linen.

The Hall Chamber

The room above the hall was a sparsely-furnished bedroom in both 1704 and 1729, holding two bedsteads topped with flockbeds – a comfortable, but less luxurious form of mattress than the featherbed. By 1729 Henry had also moved in a chest, probably the one that has gone missing from the parlour chamber.

The Cock-Loft

A cock-loft was a roofspace between the ceiling and the rafters, which wasn’t always habitable, but could evidently be used if needs must. It appears only in the 1704 inventory, when William was storing ‘one bed & boxes with other things’ up there, all valued at only 15 shillings. The ‘bed’ here is actually a mattress (the bedframe would have been listed as a ‘bedsted’) so perhaps the space was used for children or servants.

A Later Glimpse…

When William (I)’s great great grandchildren William (IV) and Mary WATSON sold the house in 1846, the household furniture included ‘Four-post and other Bedsteads and Hangings, Feather Beds, Clock in Oak Case, Oak Chest of Drawers and Table, SINGLE-BARREL GUN, 50 gallon Copper, and a general assortment of Dairy and Culinary Requisites’.2 I wonder how many of those items – like the bedsteads, hangings, feather mattresses and especially the clock – had been in the house since the time of William (I) and Henry?

- Joynd or Joined refers to a method of building wooden furniture by ‘joining’ the parts with pegs or dowels. It was the most common and simplest means of building furniture until the mid 18th century. ↩︎

[…] manorial records and learned about court rolls and copyholds. I spent a worrying amount of time delving into probate inventories and mentally reconstructing 17th- and 18th- century rooms and their furniture (ok, there might have […]

LikeLike